Dislocations: An Iranian Composer in Lesbos

/by Andy Teirstein

Viewed with a cold historical eye, it is clear that global dislocation is a key ingredient in the evolution of the arts. Would we have flamenco without the juxtaposition of migrating Roma, Arabs and Jews in Southern Spain? Imagine music without the blues (and by extension: jazz and rock), a result of the forced displacement of a multitude of West Africans. When two disparate elements come together, a fusion takes place, and a new creative force is unleashed. In this time of dislocation on a historic scale, when the “global village” has become disfracted beyond recognition from its quaint image in Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium Is the Massage (1967), the arts have arrived at a state of hyper-fusion.

On a cold March afternoon, we step into Moria, a transit camp, the European Union point of entry for the thousands of migrants who make the sea crossing from Turkey. This is a vortex of dislocation. Our concept is simple: we want to connect with skilled performing artists, and follow their progress over three years as they move from here to European cities. We hope to see how their artistic perspectives evolve, and how they affect local artists in their new locations. Prior to our arrival, a photographer friend had hooked us up with a “fixer,” a Lesbian (that is, a native of Lesbos) named Grigorio, who was able to assess the situation on the ground in the refugee camps. We registered online with the local authorities and volunteered with a representative of “Better Days for Moria,” the centerpiece NGO of the refugee camp, who would help us find a place on site to gather musicians and dancers.

The “Better Days for Moria” camp is situated in an olive grove the authorities call “Afghan Hill.” We descend from the road into a sea of men, a mixture of Afghanis, Pakistanis, Iranians, Syrians and Iraqi Kurds. Sprinkled among them are young volunteers from Scandinavia, the British Isles, and other European areas. Contrary to every expectation, there is something that can be described as pleasantness here. The men are sitting around barrel bonfires and standing in groups under trees. Some are playing soccer. There are orderly lines for coffee, cell-phone charging and first aid, a family section, and an active children’s area with toys and slides. Deeper inside we see rows of lightweight plastic housing, outhouses and water.

Photo by Cari Ann Shim Sham

People seem relaxed. We find the same sense of decorum, dignity, and repose in the other refugee camps on the island, such as Kara Tepe, a few kilometers to the south. The official in charge there, Stavros, runs a strict checkpoint, but after hearing our request to exchange music with the refugees, he welcomes us with these words: “We have no refugees here. We have only guests.”

Photo by Cari Ann Shim Sham

At Kara Tepe, we meet a group from “Clowns without Borders,” and play along with them in a parade, arriving at a small amphitheater with a large tag-along group of children and adults. The performers are Swedish—a limber blonde quartet of tumbling clowns and musicians playing accordion, fiddle and clarinet, and the audience is riveted, grinning, with wide eyes and mouths agape. For these people, most of each day is spent waiting in the limbo of unassigned status. They are hungry for this performance. Watching their faces, I recall that when we originally told people in New York we wanted to go to the island of Lesbos to meet migrant musicians and dancers, we were asked, “Why not bring them food, coats, things they actually need?”

Photos by Cari Ann Shim Sham

That evening we consider our options. While recognizing the value of the clown brigade, our own purpose here is not to entertain, but to engage in a dialogue. In preparation for this moment, world music and dance practitioners Livia and Bill Vanaver and I have spent months absorbing Syrian music, taking lessons on the oud, and learning tunes and dances we hope will resonate with the island’s transient population. We have also brought with us various musical instruments, including shakers, drums and ouds. The next day at the amphitheater, when we pull our instruments from their cases, we’re instantly crowded by faces and hands eager to try the drums and to sing. But we had been preparing for Syrians, and the makeup of the camps has now shifted to other cultural groups, centering on different instruments and tunes, and songs in Urdu and Pashtun. We have very little common language. There is a musical family of Iraqi Kurds. Bill and I launch into our one Kurdish song on oud and violin, a Bollywood one, and are gratified to find that they are excited to sing along, adding the proper lyrics. From there a series of dances ensues. Livia tries to learn a dance from them, but they’re not really including her; dancing apart, they smile at her, but there is a religious gender gap.

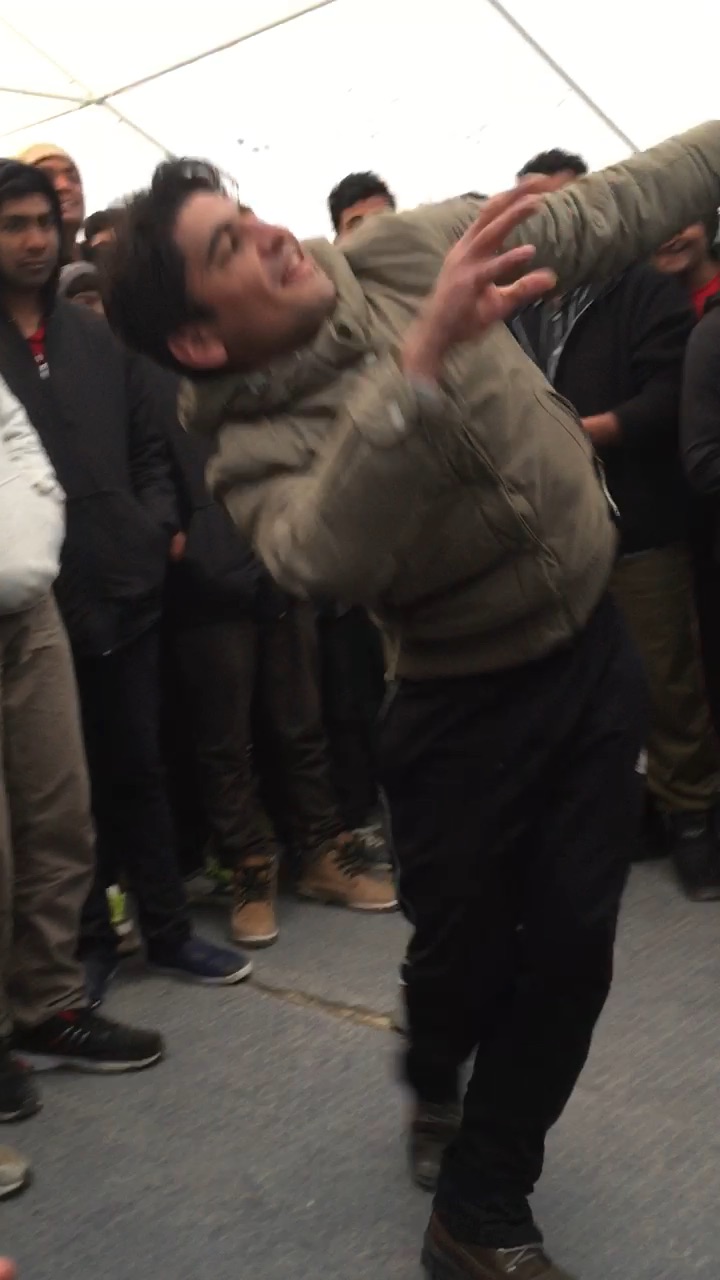

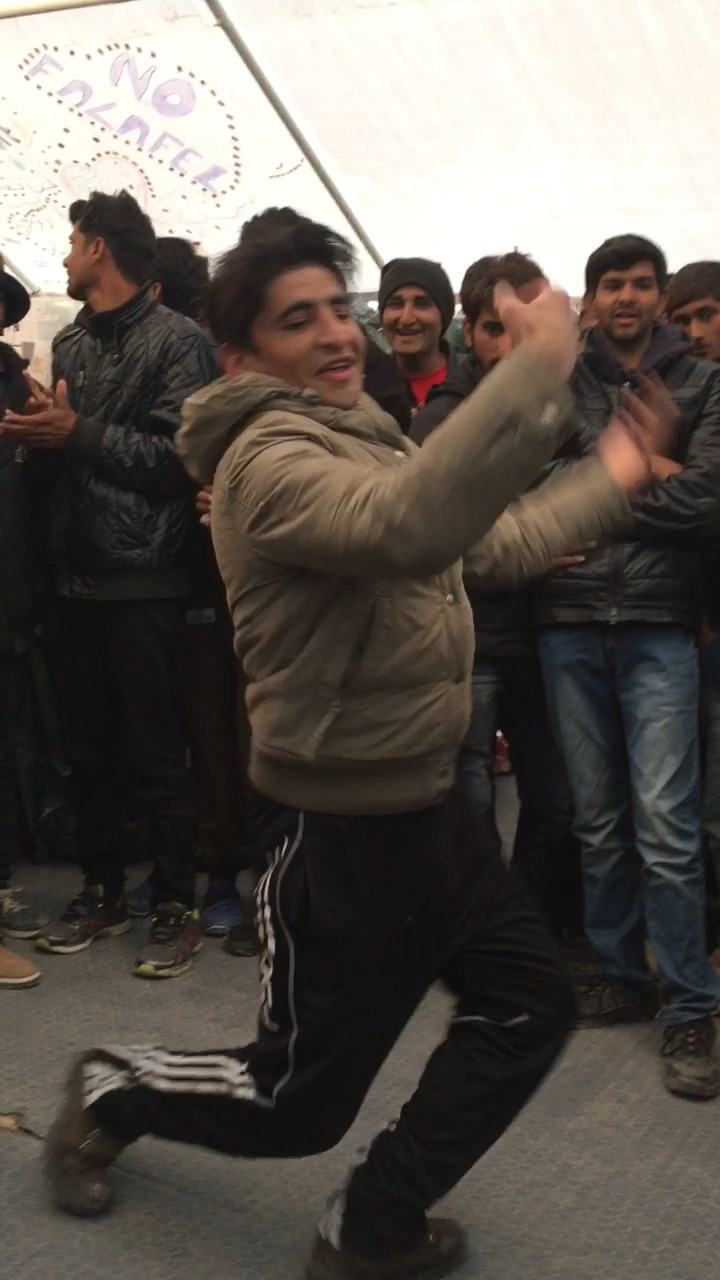

Our few days on the island are consumed in impromptu gatherings like these. Each day, the moment we arrive there are cheers and the men crowd around. In this exchange, each culture must bring something to the table. Sometimes I’ll play the banjo or fiddle, an American offering, and they are happy to reward me with one of their songs. We learn to observe subtle groupings within the swarm—the Kurds are always together, likewise the Pakistanis, the Iranians. They’re all pressed against one another, laughing, but the clumps don’t know each other; they sing in different languages. And always, we watch, for what?—for the consummate musician, the dancer who stands apart in skill, for whom dance or music may seem like it means something more to him (or, with luck, her) in itself. At one point we hear a more confident drumming from a cheery woman in traditional hijab (head covering), who is clearly a master of the darbuka drum. Her name is Fatima. When we ask her to sing she becomes shy; she is not permitted to, here. We would like to speak with her; we ask if we can meet her the tomorrow in a different spot. She smiles, head lowered, and agrees. But the next day our eyes scan the crowds of women in hijabs; we can’t find Fatima.

The instruments are the center of activity; they are physical gateways. Whoever is holding the drum seems to also hold the license to sing. The drums are passed from group to group, the excitement grows, and then, inevitably, the energy level transcends individual song and enters into communal dance. In one of these sessions we meet an Afghan dancer named Zayfula, whose movement style is carved, distinctive, and tantalizing. Later we speak with him through a translator. Zayfula is a teacher of traditional Afghani dance forms, and a choreographer. He wants to teach dance in Europe, but doesn’t know what will happen to him. Zayfula would be a perfect candidate for us, someone whose work we could follow into the future. But he has no phone, no email or Facebook account, and of course no address. We give him our card and wish him well, hoping he will reach out to us if he finds a home somewhere in Europe.

Photos by Andy Teirstein

In one of these dance and music jams, someone tugs at my sleeve. “You must meet Becca. She can get many of them singing.” Finally someone manages to find Becca and bring her into the circle. She’s a young volunteer from England who speaks Farsi and Arabic and plays the fiddle. Becca has been in the camp for three months, a witness to a blurred newsreel of faces and communities in flight. And they love her. Becca knows people. She wants us to find an Iranian musician named Kayhan, and at one point she spots him on the outskirts of our dance circle. But when he sees her beckoning him closer, he flees. Perhaps this group, largely composed of Afghans and Pakistanis, is not receptive to his music.

Photos by Cari Ann Shim Sham

Unlike the drums, the oud, a guitar-like instrument that would pertain more to the Syrian population, is ignored in our impromptu gatherings. But one day I plunk out an Arab dance tune, a dabka, and we notice a gentleman standing on the perimeter who can’t draw his eyes away from the oud. When I hand it to him, he sits and plays, his face lighting up. The rest of the group recedes slightly, listening.

Video by Cari Ann Shim Sham

We manage to pull him aside and get his permission for an interview. He is Hsam, a Syrian seeking a life of music in Europe; his brother has already made it to Berlin. We exchange information, this time more confident of a connection. With a Syrian passport, he is more likely to receive official transit papers.

Video by Cari Ann Shim Sham

Photo by Cari Ann Shim Sham

In this almost festive environment, it is an effort to recall that these are people who have fled the horrors of jihadi war or other unspeakable dangers. Along the shoreline we find discarded life preservers.

photo by cari ann shim sham

One night Livia and I come to a place on the beach where a group of Swiss are keeping watch, waiting with flashlights. They scan the water, ready to guide a stray boat in and help the refugees to the camp. I learn that refugee smugglers generally hold a gun to someone’s head and force that person to steer the boat. The smugglers push the boats off from the Turkish shore and slink away, leaving the refugees to fend for themselves. Often these inflatable boats are leaking. The motor may stop halfway across –gas runs out. The life preservers may be stuffed with paper. The journey helps explain the emotional atmosphere and peaceful coexistence in the camps. There is a palpable feeling of relief, a shared story that, for this transient moment, places historically disparate peoples into a common space.

One day we arrive at Moria to a staged protest by the Pakistanis. They are all on one side of the camp, and have asked us, the non-refugees, to film them, to “tell the world.” The Pakistanis are particularly unfortunate in that they are afraid to sign their names to any papers, thinking this might place them on terrorist lists. Whereas Syrians may receive official recognition as refugees, there is a hierarchy here, with the Pakistanis at the bottom. It is likely that they will all be sent back to Turkey, where their human rights could be violated.

Photo by Cari Ann Shim Sham

Turkey has almost three million refugees, the largest volume in world. While we were on Lesbos, Turkey was illegally returning a hundred refugees a day to Syrian war zones. Here on Moria, the protesters’ signs read “Turkey equals Death,” and “The Earth Has No Borders.” A young man leads the call-and-response chant. At one point he mimes dialing a phone, places it on his ear and shouts “Humans calling..,” to which the crowd answers “Europe!” His chant of “Thank you, Greece,” is picked up by the crowd. Then he turns to face the cameras and chants, “Volunteers, we love you.”

photo by cari ann shim sham

Video by Cari Ann Shim Sham

On our last day in Lesbos there are marches by Greek citizens through the streets of the Lesbos capital Mytilene, in support of the refugees. A group of students from a local school has painted “No Borders” on their faces. The march leads to the port, where a ship containing Pakistanis is preparing to depart for Turkey.

Photos by Andy Teirstein

That evening we stop in at Moria, and find Becca. She tells us that the Iranian musician, Kayhan, was there earlier, and may have moved to a different camp closer to Mytilene, called the “No Borders Kitchen.” Hardly expecting to find him, we drive past a castle ruin, down an unlit windy road, and see bonfires and a group of tents by the shore. When we cross into the camp, we immediately spot Kayhan, and within minutes realize that we have found the key to our work here in Lesbos. Kayhan was forced to leave Iran because he is an atheist and a composer. For us in the West, atheism is often a position of default. For Kayhan, it was a chosen conviction stated before a judge, endangering his life and the lives of his parents and siblings. The serious cultivation of music was an impossibility for Kayhan in Iran, where, as a profession it is scorned, and Islamic politics make its pursuit a personal risk. He gave his life’s savings to a refugee smuggler, packed a few musical instruments on his back and started across the border to Turkey. In the mountains he slipped on the ice and fell unconscious. When he woke the smugglers were gone. He mustered his energy, left his backpack in the snow, and hiked across Turkey, somehow managing to find the smugglers and make the crossing to Lesbos.

Video by Cari ann shim sham

Kayhan’s story is one of wrenching internal and external conflict. It also contains the glimmer of a quest. The nature of his dislocation—the degree to which it was forced or self-motivated— will be weighed by transit lawyers, whose final judgment will determine whether he will continue on to the West or be sent back to the source of his troubles. His artistic identity is also in a state of tension between two directional forces, two longings: the hope of a new home where music can be freely explored, and nostalgia for the people and culture left behind. Nostos is Greek for “a return home.” While he wishes to move into a new musical life, asking us about books on post-tonal music theory, he also carries the musical vision of his home tradition. Music is common to both directional longings. The pursuit of music provides a point of stasis for him.

“The arts too can become a home. Or make us feel more at home. Yet even more than geographical place, they have the power to disturb or exalt, and so, like the great teachings of religion, remind us that we are fundamentally homeless.”

Yi-Fu Tuan, Place, Art and Self

We leave Kayhan with a small flute, on which he plays us Persian traditional music.

As we drive past the castle ruins again, we discuss our impressions of this remarkable young composer. Kayhan has put his life at risk for the sake of his pursuit of a creative life in music. How many of us in the West can claim to place such a value on art?

Our drive to the airport takes us past each refugee camp, the volunteer tents with their coffee lines and bustling communities. Within two days, all of this will be gone. While we are in flight to New York, the European Union strikes a deal with Turkey, closing its borders to all but the most strongly-argued refugee cases. The first shiploads of Pakistanis headed back to Turkey are obstructed by refugees who jump from the ship and swim in front of its prow.

Moria has become a defacto prison. Just uphill from the place where “Better Days for Moria” stood, there is a former military facility, fenced in with barbed wire. According to news reports, it is overcrowded. Seeking asylum is a long wait; the authorities are overwhelmed. Unlike the volunteer camps, where there were separate areas, in this detention center all are herded together: men, families intact and fragmented, and a vulnerable assortment of people wounded by bomb attacks in Syria and Iraq. It is guarded by Greek police. Kayhan tells us that some people escape over the barbed wire at night. When he was approached by the police, in his best American accent he told them he was a tourist. He held his breath and walked away.

Kayhan communicates with Bill Vanaver and me through Facebook. We have been exchanging music files and discussing composers. Through Gregorio, Bill sent him a ney, a traditional Iranian reed flute. He is hungry for books on orchestration and music theory. I ask him where he is sleeping, how he is eating. He answers these questions, but it is music that he really wishes to text about.

In the month since we have returned to New York, the media has turned its gaze away from the island of Lesbos. The smugglers have shifted to targeting Italian shores. The artist Ai Weiwei recently set up a studio in Lesbos. His “Memorial to the Drowned” draped the columns of a Berlin concert hall with collected refugee life preservers. He writes, “The border is not in Lesbos. It is really in our minds and hearts.”

photo by cari ann shim sham